Hussein Askary

EIR Arabic Editor

Transcript:

When you say the word “Islamic” nowadays, it triggers associations with terrorism, extremism, and fundamentalism. Many of these associations have a certain basis in reality, but that reality is almost completely an artificial construction of political, strategic, and intelligence institutions that intend to keep the world divided and concurred. Militant Islam is a relatively modern phenomenon and became known when the United States, Britain, and Saudi Arabia financed, armed and trained the so-called Mujahideen in Afghanistan to fight against the Soviet army.

But the Muslim nations and societies themselves are also partly to blame for neglecting the great aspects of scientific, philosophical, and artistic heritage of the Islamic culture. We often hear nostalgic statements and speeches full of empty pride about “the great achievements of Islam.” But we seldom see studies and lively discussions on the details of how, when, and who created those great achievements. Everywhere you go in the Arab world, you see Ibn Sina Hospital or Ibn Sina School, AlKindi Hospital or Al-Kindi School, Arrazi Hospital or Arrazi School. But how many Arabs or Muslims today really know what those scientific and philosophical giants achieved or how they thought? And also in what atmosphere they worked and thought?

It is of course, not possible to sum up the answers for these questions, because the homework has not been done to answer them. What I want to do here is to provoke some thoughts, and urge people to do this homework, because it is urgent now, in light of the terrible things being done in the name of Islam, and in light of the terrible things being done to Muslim societies and the other minorities living within them.

Now, as I have written and presented in various occasions, the Islamic Renaissance, whose Golden Age extended from the late 8th Century into the end of the 13th Century, was not simply Islamic. It was not simply Arab, although Arabic was the lingua franca of that time from the borders of China in the East to northern Spain in the West. I may dare to say that the Islamic Renaissance was not a religious phenomenon, although it was based on the teachings of Islam which urged the believers to “seek knowledge from the cradle to the grave.” The Islamic Renaissance was rather a cultural phenomenon, a unique one, because it was a synthesis of Arabic, Persian, Greek, Egyptian, Indian, Chinese and other cultures. In Baghdad in the 9th Century you had Muslim, Christian, and Jewish scientists and translators in the House of Wisdom working without prejudice, to translate and verify Greek, Indian, Chinese, Persian, and all kinds of scientific and philosophical manuscripts. The same thing was going on in Cordoba in Andalusia, Spain.

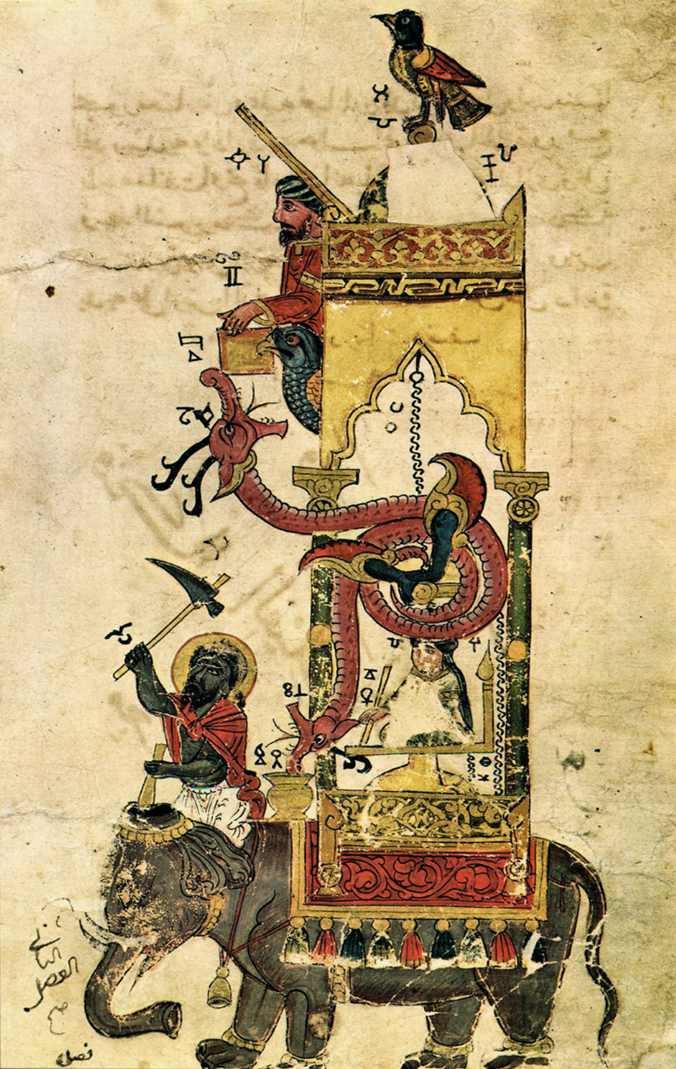

In order to give a metaphorical image of this beautiful synthesis, I chose this image of the elephant clock, a piece of mechanical and artistic work done by BadiUzzaman al-Jazari, who lived between 1136-1206 in the Al-Jazira area northeast of modern Syria. Al-Jazira means “the island,” but here it refers to the land between the Tigris and Euphrates. Hence his name, AlJazari. Al-Jazari was a true polymath: a mathematician, artist, artisan, musician, and mechanical engineer. His most known book is “The Book of Knowledge of Ingenious Mechanical Devices.” Actually the original Arabic title says something like “Combining science with beneficial work in mechanics.” In this book, he describes about 100 mechanical inventions he had made and how they can be reconstructed or built. He made miniature paintings with instructions on how to build these mechanical works. Now, what is interesting for me and for you is not the mechanics themselves, but the method of thinking, which is a great metaphor for the true dialog of cultures, of what al-Jazari had in mind, and what he understood to be the message of Islam.

But let’s take a look at one of his most known inventions, the mechanical “Elephant Clock.”

For an explanation of how the clock works, see this video! (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=doYPpgaJ0o)

Al-Jazari consciously put a phoenix bird on top, which represents the ancient Egyptian mythological deity Bennu, and is also part of Greek culture. As you may know, Egyptian and Greek were almost one culture for certain important periods, as we understand from Plato’s dialogues, and later collaboration between Archimedes and Eratosthenes, the Dean of the Library of Alexandria. The serpents or dragons symbolize China, the elephant and the deity with the cymbal refer to India, the architecture and furniture are Persian and Arabian, and the water technique is a reference to Greece.

This work, in a very beautiful and efficient way, reflects and encapsulates the whole idea of the beauty of the Islamic culture, and the spirit of the diversity in the oneness that was dominant at the time. The Holy Quran states: “O mankind, indeed We created you from one male and one female, and made you into peoples and tribes that you may know one another. Indeed, the most noble of you in the eyes of Allah are the most righteous ones.”

Can we revive that spirit today? This is the big question.

Audio (mp3):